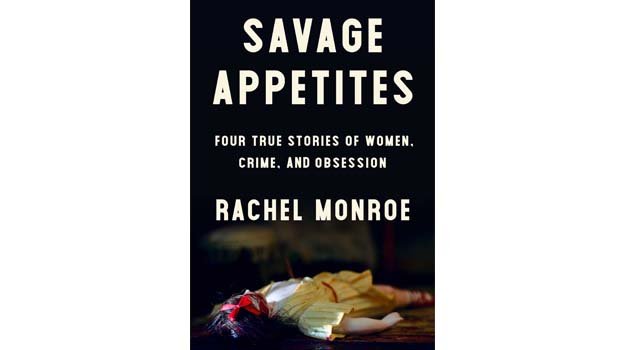

Book review

Savage Appetites

In a new, necessary and brilliant book, Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession, journalist Rachel Monroe writes: "Most of the explanations I read for why women are drawn to true crime ended up feeling reductive and unsatisfying." The explanations she had seen were that the interest was voyeuristic or feminist or self-preserving and practical. "By presuming that women's dark thoughts were merely pragmatic, those thoughts were drained of their menace," she adds."

The stories that are well-known, that get rehashed over and over again, are largely about white male perpetrators and white, middle-class, female victims, even though, as Monroe reminds us, "the people who are disproportionately at risk of homicide" are actually "sex workers, the homeless, young men of color, trans women" and, in fact, "the people who [are] most likely to be harmed by violent crime [are] young black men from low-income neighborhoods."

So why do we find true crime fascinating? How are we relating to it? Who is telling what stories and why? Monroe doesn't have one distinct answer for us — nor, I suspect, does she believe there is one — but she showcases several women, each with a different relationship to the genre. Frances Glessner Lee, considered by some the "mother of forensic science," is the first; second is Alisa Statman who, whether in good faith or not, inserted herself into the lives and stories of Sharon Tate's family; third is Lorri Davis, who ended up marrying and helping to free Damien Echols, who spent years on death row after what is widely believed to be his wrongful conviction for the murder of three small boys in West Memphis; and, finally, Lindsay Souvannarath, sentenced to life in prison in Canada after she and another young adult she had met online planned to vaguely emulate the Columbine shooters by wreaking havoc in a mall in Halifax (they never got that far).

Monroe's book is a pleasure to read because it is smart, well-researched and well-written — beautifully, really, as each of the four long chapters takes the form of a braided essay that links two and sometimes three distinct stories together, showcasing Monroe's own obsessions alongside those of the real-life characters she explores.

While Monroe has the role of journalist here, probing the history, motives and psyches of her subjects, she also interrogates herself by weaving her stories into those of others.

So it's not without doing the work herself that she urges us not to turn off our brains in the pursuit of true crime's anesthetizing effect: "We can use [sensational crime stories] as opportunities to be more honest about our appetites — and curious about them too."