Director’s Directory

Iranian renegade Abbas Kiarostami

The most acclaimed and influential of Iran’s major filmmakers, Abbas Kiarostami, was born in Tehran on June 22, 1940. Raised in a middle-class household, he was interested in art and literature from an early age. During and after university, where he majored in painting and graphic design, he illustrated children’s books, designed credit sequences for films, and made numerous television commercials. In 1969, he was invited to start a filmmaking division for the government-run Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (an organization Iranians call Kanoon).

Kiarostami’s deliberate blend of fiction and reality delve into the deeper aspects of the human condition. His background as a painter, poet and photographer provide a richly sensual foundation for his work and garnered him accolades as he rose to prominence in the early 1990s. His fusion of fiction, nonfiction, and self-dramatizing reflexivity advanced the art of cinema, and it became emblematic of the Iranian cinema over all, which Kiarostami rendered central to the time.

The ten-minute Bread and Alley (1970) was the first of several short films, most centered on children, that he directed over the next two decades, a period during which he also made documentaries, including the feature-length First Graders (1984) and Homework (1989), both of which take up the subject of education. His first narrative feature, The Traveler (1974), about a provincial boy scheming to reach Tehran to see a soccer match, was made under Kanoon’s auspices, while his second, The Report (1977), an autobiographically tinged story of a collapsing marriage, was made independently.

Most modern filmmakers started fast and made their names with their first or second feature; Kiarostami, by contrast, worked like a studio filmmaker of the silent era, developing styles, themes, and ideas gradually, along with their craft, before synthesizing them into a grand body of work. He made more than a dozen short films, as well as a handful of features, before making “Where Is the Friend’s House?,” from 1987, which brought him international prominence.

Many of Kiarostami’s early films were made before the 1979 Islamic Revolution; even if they were subject to the political censorship that prevailed under the Shah’s rule, they didn’t face the religious restrictions that were enforced by the new regime. They show a diverse Iran, in which some women wear headscarves and others don’t; they more freely discuss and depict relationships between men and women, as in the most intricate of his short features, “Experience,” from 1973. It’s a story about a fourteen-year-old boy who works as an assistant in a photography studio, a tale in which the making of images, and the making of a living from them, is at the core of the action, which ranges widely through the city to reveal secret passions that energize daily lives.

The documentary-based minimalism of filming in public, the implication of offscreen space in sequences of “Experience” that, for instance, hang back on the outside of a building and observe entrances and exits, or witness action in fragmentary detail through distant windows, was one of Kiarostami’s crucial visual motifs. It’s even more emphatic in a companion film, “A Wedding Suit,” in which a poor boy who works as a tailor’s assistant is forced to lend a bespoke suit to another teenager who wants to wear it to impress a girl on a date.

It was after Iran’s 1979 revolution that Kiarostami began his rapid ascent to international renown. Where Is My Friend’s House? (1987), about a rural boy’s effort to return a pal’s notebook, won the Bronze Leopard at the Locarno Film Festival. Close-up (1990), about the trial of a man accused of impersonating a famous filmmaker, was the director’s first film to focus on cinema itself, and the blur the lines between documentary and fiction; it has been voted the best Iranian film ever made by Iranian and international critics.

In And Life Goes On (aka Life and Nothing More…, 1992), he dramatized a journey he made into an earthquake’s devastation zone to discover if the child actors of Where Is My Friend’s House? have survived. Those two films and Through the Olive Trees (1994), which dramatized the making of And Life Goes On, have been dubbed the “Koker” trilogy by critics after the name of the village where much of their action was filmed.

After And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees earned Kiarostami wide acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival, his next film, Taste of Cherry (1997), became the first – and so far, only – Iranian film to win the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or. Telling of a man’s attempt to gain assistance in committing suicide, a taboo under Islam, the film was one of several by Kiarostami to be banned in Iran while enjoying international success. His final film of this remarkable period, The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), which concerns a camera crew on an enigmatic assignment in Kurdistan, won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

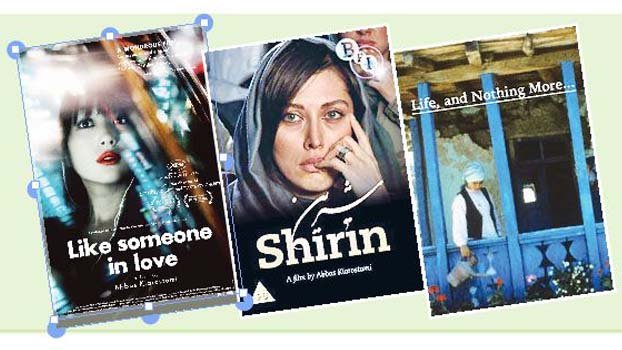

In the new century, Kiarostami broadened his creative focus, devoting more time to forms including photography, installation art, poetry, and teaching. In cinema, he embraced low-budget digital filmmaking for the feature Ten (2002), the documentaries ABC Africa (2001) and 10 on Ten (2004), the experimental films Five (2003) and Shirin (2008), and several shorts. Beginning at the decade’s end, he went abroad to make two dramatic features, both centering on male-female relations: Certified Copy (2010), starring Juliette Binoche, in Italy, and Like Someone in Love (2012) in Japan. At the time of his death, he was preparing a movie to be made in China.

In March 2016, while he was in the midst of working on 24 Frames, Kiarostami was hospitalized and underwent several operations. He was transferred to Paris in late June of the same year, and died there on July 4th. Charges have been made that his death was caused by medical malpractice by doctors in Iran. He is buried in Lavasan (a small city near Tehran). Posthumously completed, 24 Frames premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2017.