Australia as Japan’s regional partner of choice

Australia released its new International Development Policy for a Peaceful, Stable and Prosperous Indo-Pacific in August 2023, which coincided with Japan’s Cabinet revision of its Development Cooperation Charter. This raises the question of whether Australia’s new policy is responsive enough to its neighbours’ needs and priorities to make Australia their ‘partner of choice’.

Australia’s policy emphasises partnership on an equal basis. Minister for Foreign Affairs, Penny Wong, called for ‘genuine partnerships based on respect, listening, and learning from each other’ with neighbouring countries. This implies that Australia is committed to not imposing its models on its partners.

While Japan’s charter also refrains from advertising its development models, it does refer to ‘a systematic approach to learn from Japan’s experience’. This may sound outdated for developing countries considering the changing global development landscape. Japan’s emphasis on the ‘co-creation of social values through dialogue and cooperation’ aligns with Australia’s approach.

Australia’s policy addresses common global issues, such as ‘climate change, global economic uncertainty, demographic and technological shifts’. It also considers gender and social inequalities, while hinting at complicated geostrategic challenges. Still, it could be more explicit about its guiding principle.

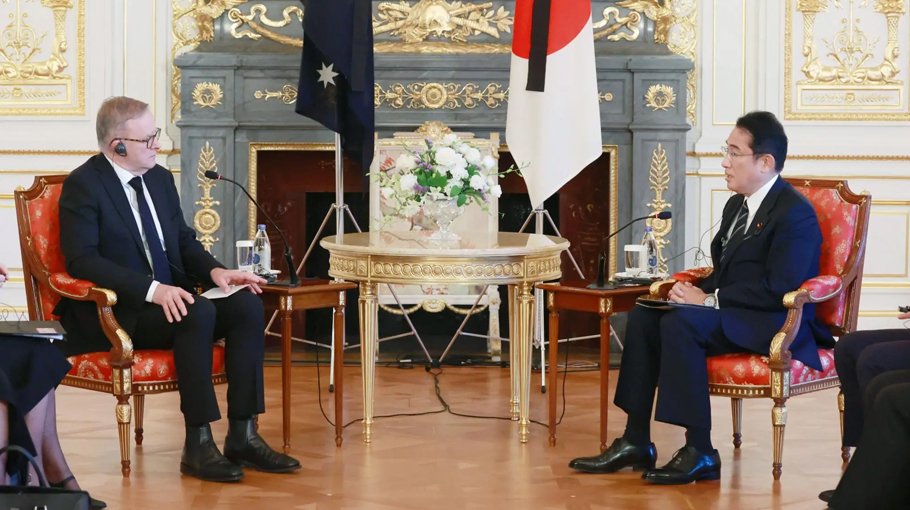

By contrast, Japan’s charter explicitly presents its core principles of development cooperation, such as human security and a stance against military cooperation. This posture mirrors Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s recent United Nations General Assembly address, which emphasised ‘human-centered international cooperation’ and ‘human dignity’.

A salient feature of Australia’s policy is its regional focus as explicitly stated, for example, in the statement: ‘the Indo-Pacific will remain the focus of Australia’s development program’. The Indo-Pacific, particularly the Pacific, is Australia’s target region.

On the other hand, Japan’s charter leans more towards a bilateral approach. It refers to the Indo-Pacific in the context of the geopolitically motivated Free and Open Indo-Pacific initiative. Given this, the charter may be actually targeted to domestic stakeholders with differing priorities rather than the leaders of developing nations.

Australia’s policy sounds apolitical and commits to a more effective and responsive delivery of its development program while subtly considering the geopolitical context of the region. The mention of ‘geostrategic competition’ reflects concerns about global vulnerability and instability. Australia’s policy also refers to the ASEAN Outlook, suggesting a preference for ‘a strategic equilibrium’. While Australia is not explicit about national security, it gives development objectives a common posture in line with its Defence Strategic Review.

Japan’s charter, by contrast, is scattered with political messages aligned with national security concerns. This gives the impression that Japan has a broader political agenda beyond development cooperation. Yet, some interpret the charter as a step towards an ‘aid-security nexus’ and the use of official development assistance (ODA) as a tool for ‘strategic competition with China’.

Such messages have raised concerns about the compatibility of Japan’s charter’s stated purpose of overcoming ‘compound crises by transcending differences in values and conflicts of interest’. References to contentious topics, such as ‘debt traps’ may also embarrass China and partner developing nations because ‘political-economy dynamics and governance problems’ of borrowers sometimes ensnare them in unsustainable debt.

All of Japan’s politically motivated messages, which seem to implicitly exclude China, may bother developing nations who are unwilling to take sides. Australia’s policy is carefully crafted to avoid such risks. It could serve as a tool of statecraft to influence a target counterparts’ behaviour. This approach acknowledges that developing nations prefer to take a ‘friend to all, enemy to none stance’ when engaging with their partners.

Toshiro Nishizawa is Professor at the Graduate School of Public Policy, the University of Tokyo.