Book Talk

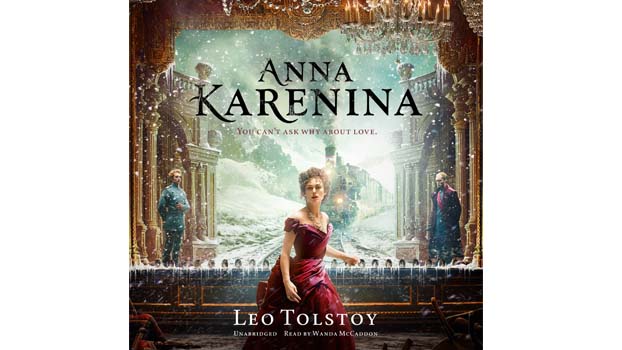

Anna Karenina

by Leo Tolstoy

Angela N Blount

‘Anna Karenina’ is a sweeping, ambitious story that weaves through lines between three primary couples: Stiva and Dolly, Anna and Vronsky, Levin and Kitty. And while we’re given time in the POV of each of these characters, Tolstoy expands his omniscient 3rd-person limited offerings out to include Anna’s legal husband Karenin, her 8-year-old son, and even Levin’s hunting dog, Laska.

The writing is often lyrical — evocative, even — but oh-so wordy. I’m pretty sure a solid 1/3rd of it could have been trimmed with no detriment. Indeed, it would have to be cut down at least that much if one wanted to see it published in today’s literary market. Preferably removing some of the approximately 1,000-page parts detailing the political dilemma surrounding peasants and their apparently lackadaisical work ethic. (Yes, I exaggerate.) I’m sure this was some sort of real issue during Tolstoy’s time, but good grief.

To be fair, the book wasn’t nearly as dull as I always feared it would be. It actually reminded me of Jane Austen on numerous occasions — which is surprising, given it’s a Russian work. I think this was due to some combination of the time period, flow, depth of internal thoughts, and keen societal observations.

It didn’t hurt that Tolstoy was pretty clearly calling out the ridiculousness of Russian laws surrounding divorce.

I was impressed I was able to like and sympathize with Anna at first — being unaware of how loveless her marriage to a much-older emotionally constipated civil servant is until she’s presented with the excitement of a passionate, obsessive suitor. I sympathized all the way up until she comes home from her flirtation with Vronsky and finds her own son disappointing. It’s completely believable. I’ve seen it before in women who are so consumed with a new love interest, their own children fade in significance… But I can’t help finding that priority shift repulsive.

I have to give Tolstoy a lot of credit with his foreshadowing. Anna’s ominous dreams are repeated often enough to pique curiosity, and their overlap with Vronsky’s drives it to a point of urgency. The scene of the horse race was particularly poignant a device — as it not only marked a dramatic turning point in the plot, but highlighted Vronsky’s recklessly narcissistic nature. (view spoiler) Had Anna not been too far emotionally compromised, she might have seen this as a glaring sign she ought to run far and run fast.

Another aspect of Tolstoy’s writing worth mentioning, and perhaps my favorite, was his surprisingly solid grasp on the female psyche. Here we have the POVs of several very different women, oppressed in different ways by society and gender perceptions. And every one of them felt like real, well-rounded people. Tolstoy is the first of the classic male authors I’ve read who truly seemed to understand how women feel and think — and WHY. (To be honest, I’ve felt this way about precious few modern male authors.) When I was in the head of one of Tolstoy’s female characters, I never once was pulled out of the story by some awkward misstep that made me think, “Oh right, this is a dude pretending he can think like a woman.”

By the end of the book I came to realize… I didn’t really like any of these characters.

I pitied Dolly and Anna for the situations their own society and emotional overruling seemed to trap them within. And Kitty’s frail, naïve perfectness finally eased off in annoyance by the final few chapters. I found Steva, Vronsky, Karenin, and Levin all insufferable in remarkably different ways. But ultimately the only sufferer of this massive soap opera who I truly wanted the best for was Anna’s neglected little boy.

I mean, Levin’s dog seems okay, but that’s hardly something to keep me invested.